You might have tens of quoins in your letterpress set-up. They seem to multiply in my works, and I occasionally turn up a cache of quoins that seems to have appeared overnight. Printers need a solid surface from which to print and quoins are the devices that force everything in the forme against each other to hold everything in the chase together.

Wedge-Type Quoins

The first way of getting material to expand and fill space was to have two wedges, acting against each other to push outwards. These were originally wood, with a special tool — a shooting stick — used with a hammer to force the two wedges to expand by being forced against each other. The May and June British Printer for 1912 commented on the continuing popularity of the primitive pair of wooden quoins.

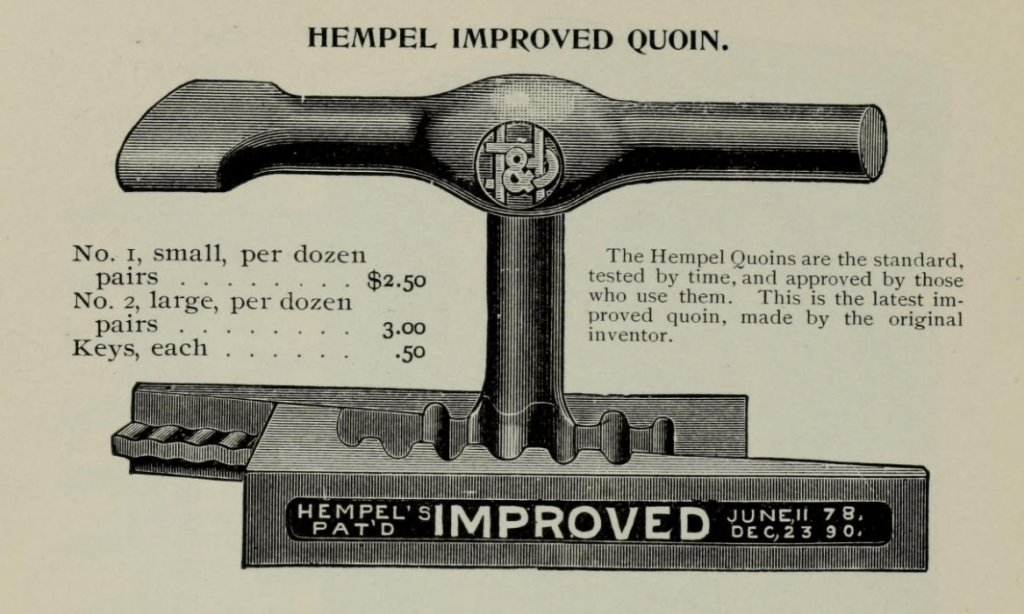

This was refined with cast iron wedges having both a channel inside and teeth so that they would mainly move left and right, rather than in all directions, and so a cog-shaped key could be used to drive the quoins apart. These are Hempel quoins and while using the same principles as the first wooden quoins were still in widespread use at the turn of the 20th century.

Wickersham Quoins

The problem with wedge-type quoins is that as a printer you need them to move outwards to fill space, not left-to-right. Wedge quoins could only move outwards if they moved sideways and this additional movement had a tendency to disrupt the other items in the forme, especially spacing material.

Wickersham quoins were developed with a cam inside that could be turned with a key on top. Springs at either end of the quoin held the outside faces against the cam. This action meant that the quoin for the first time just pushed outwards to fill space.

One frustration of a Wickersham quoin is that as the cam moved through a complete revolution, it would go back to the start point. In practice the quoin could be opened too far and click back in to the original position.

Notting Quoins

As printing became more and more precise, better registration was needed (for colour work, for example), and presses ran at higher speeds a better solution was needed to meet a large number of criteria. These included the need to have a positive action, be light, be precise, be possible to calibrate.

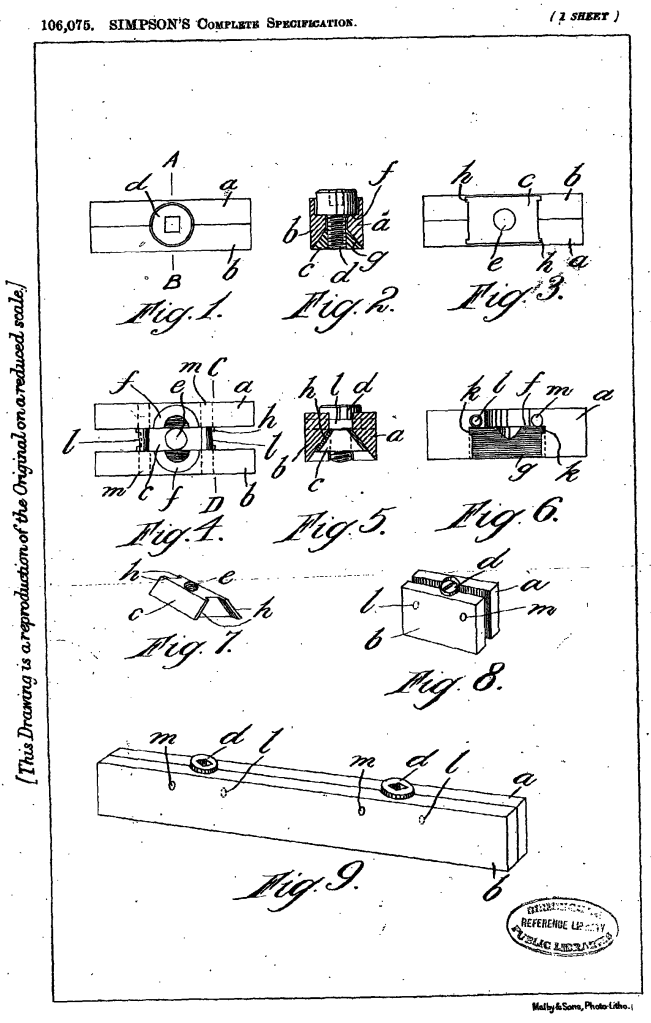

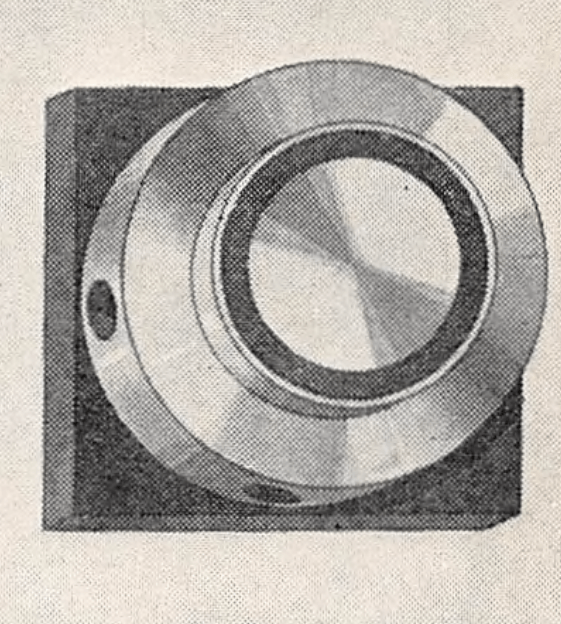

In 1917, Percy Simpson of the engineering firm Notting, of Farringdon, London, patented a new type of quoin. This held a wedge lifted by a screw. As the wedge lifted up this forced the inside of the quoin apart. Either side of the quoin was pinned together to hold all the components in place.

Notting Quoins utilise the screw and wedge system and are therefore very powerful and free from any tendency to slip in use. They are made of steel and accurately machined on all working surfaces, to give completely parallel sides at all stages of expansion with consequent freedom from springing. The expansion for one turn of the screw is relatively small, so that the quoins take longer to lock than the simple wedge or cam types, a fault more than recompensed by their security.

Print in Britain, 1954 — Productivity and Precision – Pre-Makeready

A further advance was the 1957 patent to amend that design slightly — rather than a flat wedge inside the quoin, this was changed to a convex or curved shape, meaning that only a short strip of metal was in contact with the inside of the quoin at any time. This, claimed C. F. Moore & Sons, would avoid the tendency of Notting quoins to lift slightly as they were tightened.

In a British Printer article of 1960, W. J. Higgs suggested this lifting tendency was driven not by the quoin but by other inaccuracies in the forme. Flat-sided wedges in this set-up would exacerbate the inaccuracy. Having a convex wedge means that the quoin can accommodate some of these inaccuracies.

Specialist Quoins

Having covered the basic types of quoin, there are a few specialist items associated with quoins, driven mainly by the drive to make letterpress printing more and more precise.

Some quoins carry a means of indicating how open or closed they are. On the quoin above the pin in the channel to the left of the key hole shows how open the quoin is. In some other cases, the key-hole at the top of the quoin has positions marked. This was essential to accurately re-position materials in the forme, especially colour work where laying down a fine screen of a second colour had to be in perfect alignment with the first screen.

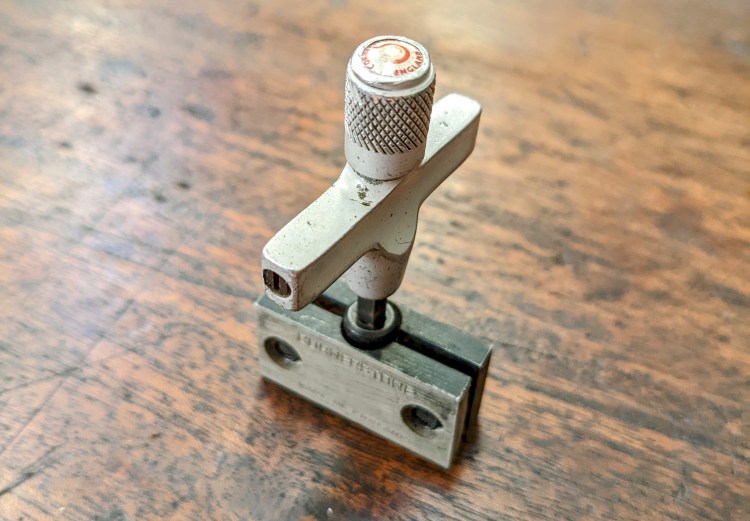

A smaller quoin, the precision register quoin, was designed for use in register work so that they could be arranged around each block — allowing movement in any direction without disturbing adjacent blocks or type. This was in the form of a screw on a plate, the screw being turned with a pin.

Finally a torque quoin key was available. This helped precision because it avoided over-tightening. The key could be set to allow only a certain force to be deployed to tighten quoins, and would ‘trip’ once that force was exceeded.

Quoin Care

One final word: mechanical quoins are precision built. The working parts need lubrication if the quoins are to give long and efficient service. Servicing, therefore, should be a more thorough and regular routine than it is at present in many printing offices!

Print In Britain, 1960

Year and Era

1917, as the date of the Notting Patent / Commercial

Object Type

Other Objects

Location

Bowling Green Lane, Farringdon, London as home of the Notting Works during Percy Simpson’s patent application.

An Appeal

If you have something linked to this object, please get in touch.

Header Image: from front to back — small Cornertsone quoin and key; usual side Cornerstone quoin; Hempel cast iron quoins; Hempel key; shooting stick. Authour’s collection.