This article is published in commemoration of the demise of Her late Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

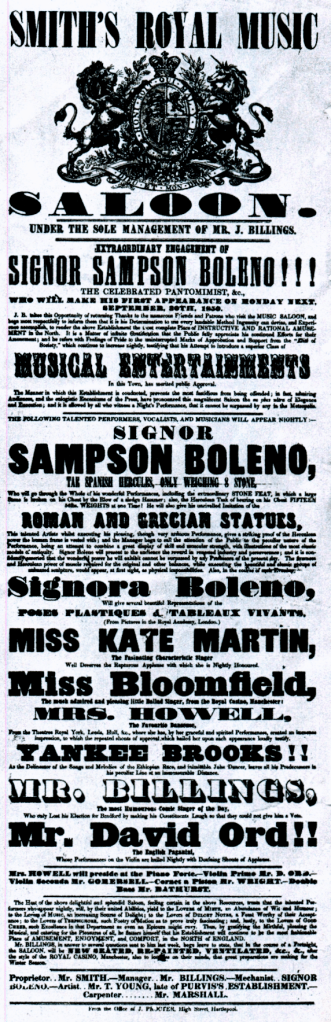

Royal Arms have always conferred an air of authority on printed items and printers have sought to use this in their work.

History of the Arms

In 1492 De Worde added the arms of Henry VII at the end of a Statute, but there wasn’t always a direct link between royal authority and the printed piece. Many printers used the Royal Arms just as decoration.

For a period, printing was licenced through Royal prerogative. The Arms in this case reflected the printer’s permission to print, rather than expressing that the printed item was authorised in any way by the Crown.

As government printing work began to grow, printers have had a ‘standing invitation’ to bid for work from what was Her Majesty’s Stationery Office (HMSO). This printing demanded that the Royal Arms were included, but HMSO did not supply a standard printing block to use. Edmund Fry & Co included a block in their 1790 catalogue. Carter1 suggests that there appeared to be no standardisation of appearance until the suggestion that around 1902, founders’ specimen books began to refer to Arms as ‘authorized by H. M. Stationery Office’. In fact this was the result of a discussion between the Controller of HMSO and the Home Office. The design authorised was very weak, and printers still used the variants that had been produced by founders.

The 1922 report of The Best Faces of Type and Modes of Display for Government Printing Committee lavished attention on the Royal Arms. The Committee recommended different drawings to be used at different sizes — earlier large Arms had simply been reduced losing detail and clarity — and that the Arms always be placed at the head of the document.

The 1956 Reynolds Stone Arms

By 1954, the 1920s arms were dated. The ‘snowstorm’ background was inappropriate, printing and reproduction had advanced, and crucially, Her late Majesty had expressed a wish that the St. Edwards Crown should replace the earlier Tudor Crown.

The wood engraver Reynolds Stone was invited to create a new design for the Arms. He created designs at two sizes to allow for intermediate sizes to be developed so that the Arms could be printed with an appropriate level of detail at different sizes. There were nine approved versions of the 1956 Arms.

Some Scottish and Northern Irish printing did not have to use Reynolds Stone’s design, but for all other uses, Her late Majesty approved the design for use from January 19562.

Royal Cypher

The Royal Cypher has a slightly different role, being individual to the monarch rather than representing the authority of the Crown. While it’s usual for us to see the EIIR cypher and the Reynolds Stone Royal Arms together, the Royal Arms adopted in 1924 would have been used by George V, Edward VIII and George VI but their Royal Cyphers are each different.

Queen Elizabeth’s cypher was needed for her coronation in 1953 not least to be embroidered on to the uniforms of the Royal Household.

Being Queen Elizabeth the Second was not taken for granted in Scotland, and a case was brought by John MacCormick arguing that since there had been no Queen Elizabeth the First in Scotland (being only Queen of England), then Queen Elizabeth could not be Queen Elizabeth the Second in Scotland. The case failed, the Queen being able to call herself whatever she wished. Despite this legal failure, some pillar boxes were attacked that bore the EIIR cypher. As a result the Royal Mail in Scotland adopted the Crown of Scotland as an emblem, rather than the EIIR cypher.

Restrictions on Use

Noting earlier that the use of the Arms did not always carry authority, attempts have been made to restrict use of the Arms. The Board of Trade seemed to change tack on use of the Arms in the late 1800s — an 1884 letter explained that their use was only restricted if they were used with intent to deceive. But by 1894 the Board advised that only a court could decide whether printers could use the Arms on their work without authority.

Charles III

King Charles III will have to decide on a Royal Cipher. The Ministry of Type looked at Royal Insignia and proposed a suggestion in 2009 of what a CIIIR cipher might look like, based on what looks be to Caslon used on earlier ciphers.

Charles might also wish to look again at the Royal Arms. Despite their last update being 66 years ago, it feels difficult to see how it can be improved, although a tweaked version for digital reproduction has been used in the HM Government Identity System.

Year and Era

1956 / Modern

Object Type

Other Objects

Location

Buckingham Palace, London, as the likely location of the approval of many versions of the Royal Arms.

Sources and More Information

- Carter, Harry, Printers’ Royal Arms to 1956 in Penrose Annual, 1957

- Letter from the Office of Public Sector Information, 2006

An Appeal

If you have something linked to this object, please get in touch.

Header Image: Authour’s Royal Arms